After finishing Brunelleschi’s Dome, Ross King’s book on the apex of architectural and engineering innovation during the Italian Renaissance, I flipped to the copyright page and noticed, near the very bottom, the following sentence:

Set in Bembo

I noticed too that the sentence is un-punctuated, which did not strike me as exceptionally odd—especially after checking at random the copyright page of a few books on my shelf, and finding among them no convention or consensus regarding the inclusion or formatting of a sentence denoting the book’s type. Nevertheless, the detail stuck out enough for me to remember it.

I’d recently read about Bonifacio Bembo, a Renaissance painter patronized by the Sforza family who is often simply called Bembo. Curious, and certain it wasn’t coincidence, I Googled. I wondered—mostly because he was the only Bembo of whom I knew, but also because the artist was, well, an artist, and one who was alive when the famed dome was completed—if the typeface in which a book about Italian Renaissance architecture is set, is named for an Italian Renaissance painter. A loose association, sure. But there are things that make less sense.

Turns out the typeface is named for a Bembo—but not Bonifacio.

*

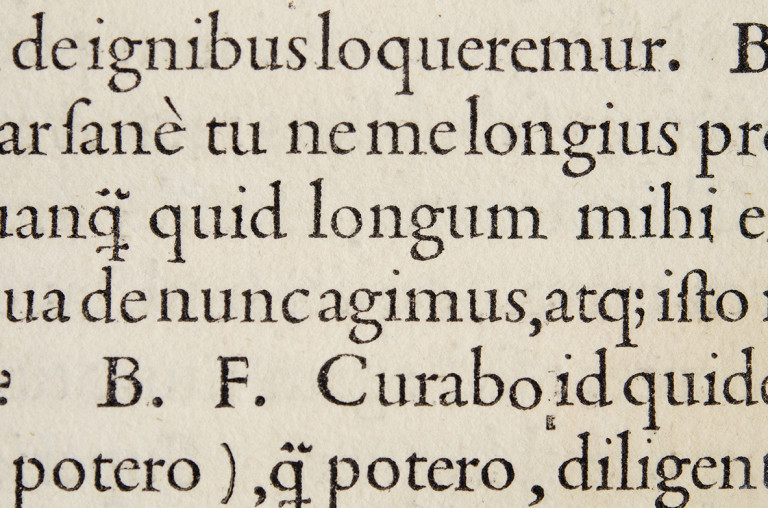

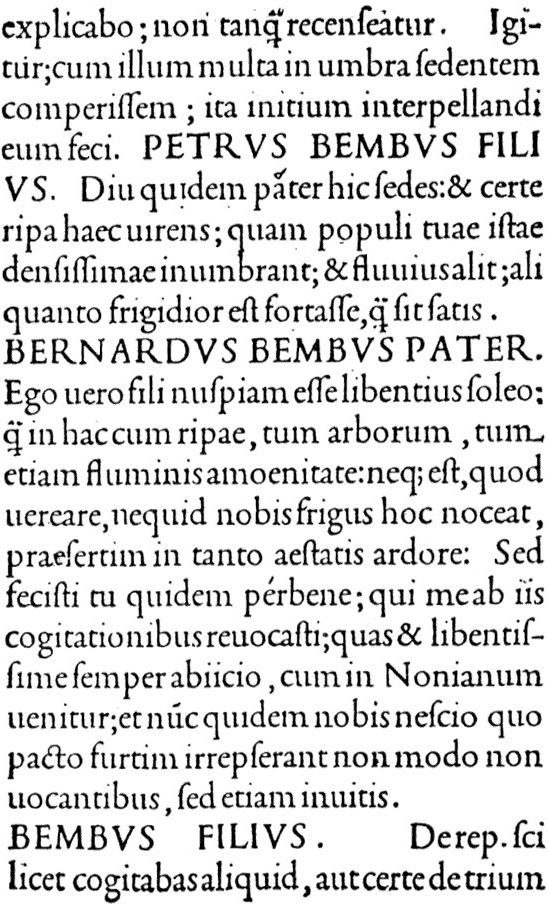

Born into a patrician family, Pietro Bembo was many things—the son of esteemed humanist Bernardo Bembo; one-time lover of Lucrezia Borgia; Venetian historiographer; papal secretary; cardinal; and, most relevant here, poet, librarian, grammarian, and scholar.

This Bembo successfully argued for, and then codified, one of the earliest Italian grammars, and was instrumental in establishing the Italian literary language. It makes much more sense, then, that the typeface is named for him, and not the painter Bembo.

Pietro Bembo was also a friend and collaborator of Aldus Manutius, a popular and prolific Venetian printer and publisher. A man of innovation, Manutius made significant—even revolutionary—contributions to printing and publication during the Italian Renaissance: his Aldine Press was the first to print italic type; he introduced and normalized the use of punctuation in print; and he invented the precursor to today’s paperback—soft-covered pocket-sized editions of texts, which made such works not only portable, but also affordable and, therefore, accessible.

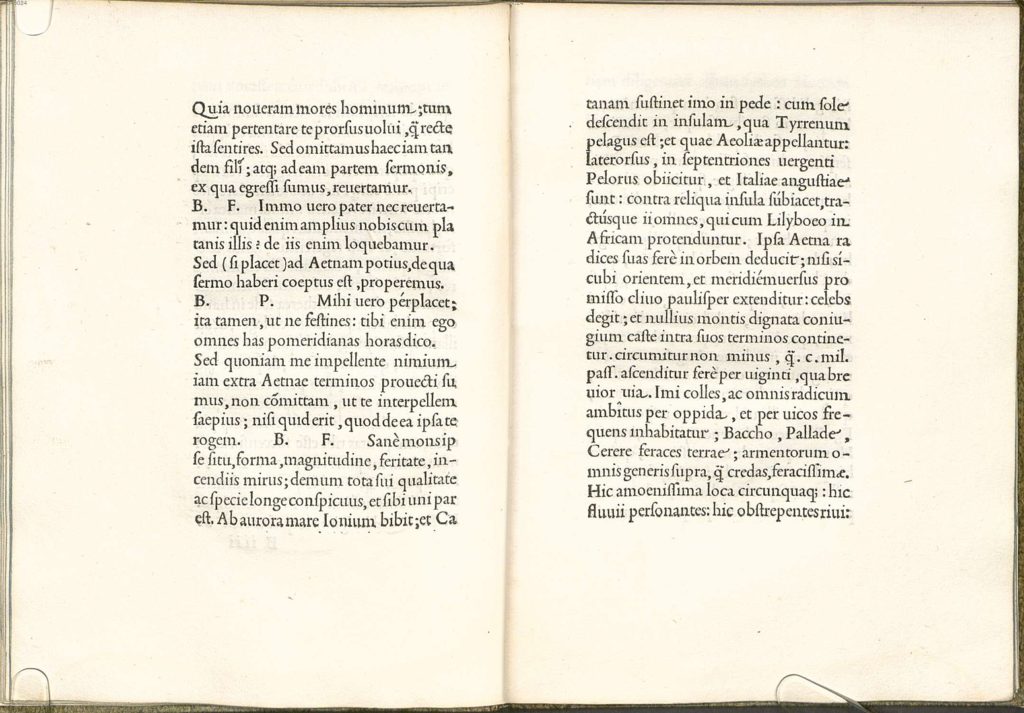

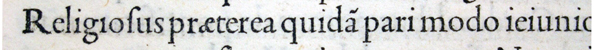

In 1496, Manutius published a 60-page travelogue by Bembo titled De Aetna.1 The text, which documented Bembo’s ascent of Mount Etna,2 was printed in a roman type designed the year prior specifically for the work by punchcutter Francesco Griffo. The type was a distinct departure from the pen-drawn script and calligraphy popular of the day, and is considered a landmark in typography:3

“In February 1496, Aldus published a rather insignificant essay by the Italian scholar Pietro Bembo. The type used for the text became instantly popular. So famous did it become that it influenced typeface design for generations. Posterity has come to regard the Bembo type as Aldus’s and Griffo’s masterpiece.” —Allan Haley, Typographic Milestones

In addition to its technical typographic triumphs, De Aetna is also considered a landmark in Italian literary history: it is Bembo’s first Latin work, it is the first of his works to be printed, and it is the first Latin text printed by Aldus Manutius.

It is also the first printed text to use the semicolon as punctuation4 (it is this bit I find most interesting), and, as Roderick Conway Morris wrote in the New York Times in 2013, was hugely influential on the design and format of ~the book~ as we conceive of it today:

“With its clean design, wide margins and beautiful typeface engraved by Francesco Griffo, this small volume [De Aetna]…was the prototype of the modern book and of the pocketbook, a revolutionary format that brought enormous success to the Aldine Press.”

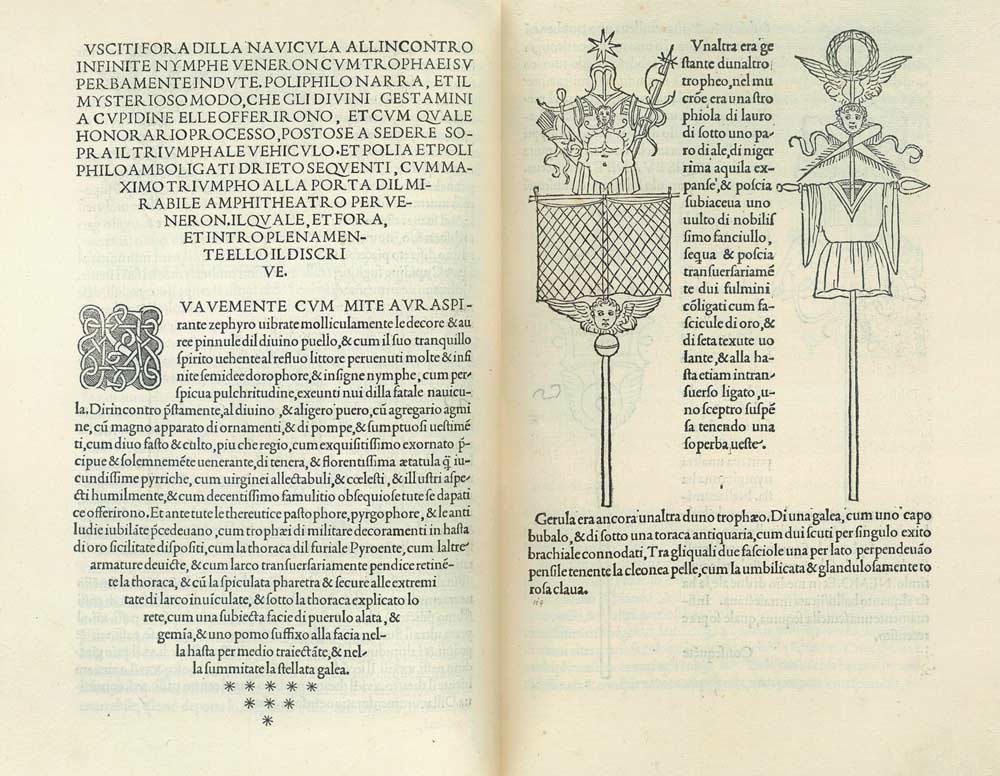

A version of the De Aetna type, improved and recut by Griffo, was used by Manutius three years later to print Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, a beautiful and strange work, unique (and celebrated) for its design and incorporation of illustration.5

The modern revival of the quattrocentro roman type—a redrawing of Griffo’s De Aetna design—was led in 1929 under the direction of Stanley Morison of the Monotype Corporation, and is the Bembo typeface we know today.6

So, there it is. The answer to the question that started this all: The type in which my copy of Brunelleschi’s Dome is set is indeed named for a Renaissance man, though not the one I originally presumed. And the history of not only the typeface itself but also that of the man for whom it is named, as well as that of both the printer and the punchcutter ultimately responsible for its design, is much more interesting than I expected.

*

The day after I first took to Google and learned it was not the painter Bembo for whom the typeface is named, but the poet/librarian/grammarian/scholar Pietro Bembo, I made my weekly visit to the National Gallery of Art. While wandering through the Italian galleries, I paused in front of a portrait I’d passed many times before, this time taking a moment to read the placard placed on the ledge beneath: Cardinal Pietro Bembo by Titian. Heh. Full circle, or whatever.

*

While my initial curiosity was, rather simply, a question of whether or not a book about Italian Renaissance architecture is set in a typeface named for an Italian Renaissance painter, as I learned about the man for whom Bembo is named, and of the innovations of the man who first printed Bembo’s work, I had new questions. After all, Bembo is not the only modern version of a quattrocentro type7—Brunelleschi’s Dome could have been set in any of a number of revived Renaissance typefaces. But it was set in Bembo. And about that, I had two new questions.

I wondered: Was the decision to print a book documenting architectural innovation during the Italian Renaissance in the Bembo typeface intentional because of the typeface’s association to innovation in Italian Renaissance printing, and if so, while it was the semicolon, not the period, that appeared as punctuation for the first time in Manutius’s printing of Bembo’s De Aetna—and so not an exact parallel—was the decision to not end the sentence on the copyright page with punctuation also an intentional, albeit ironic, nod to Aldus Manutius’s influence on normalizing the use of punctuation in print?

I emailed the book’s author to find out:

“I suspect…that Bembo was chosen in part because of its links to the Italian Renaissance. I don’t think punctuation [on the copyright page] was omitted as a tip of the hat: I’ve just looked at a book on my desk and it says ‘Set in Garamond’—with no punctuation either.”

A happy coincidence, then, it seems. Or perhaps not, given the typeface’s continued popularity, especially for the publication of books. (And how fitting that the book Mr. King checked is set in Garamond, as the Garamond typeface is modeled upon the same Manutius-commissioned/Griffo-cut quattrocentro type as Bembo.)

Notes, etc.

- Ross Kilpatrick’s English translation of De Aetna—The ‘De Aetna’ of Pietro Bembo: A Translation—is available on JSTOR and EBSCOhost. Both databases paywall the article, however both databases have partnerships with academic institutions and local libraries that provide free access to students and patrons. Check if your institution is partnered with JSTOR; check directly with your institution to learn if it is partnered with EBSCOhost.

Cambridge University has in its collection a De Aetna first edition, which belonged to, and is marked up with emendations for its next printing by, Bembo himself. The text was donated by Stanley Morision to the Monotype Corporation after he purchased it in April 1940. The Corporation gifted it to the university library in 1967. - Mount Etna is the largest volcano in Europe and for centuries has been one the most active and most monitored in the world. Aetna Insurance Company, the original parent company of the Aetna Inc. with which we are familiar today, initially dealt primarily with fire insurance and is named after Mount Etna.

- More than 500 years after it was first cut, Griffo’s De Aetna typeface is still relevant, and its influence is evident in many popular modern typefaces, particularly Garamond and Times New Roman. In fact, nearly all of the “old style” typefaces—not just Bembo, Garamond, and Times New Roman—can be traced back to Griffo’s De Aetna type. Here are a handful of examples of Bembo in contemporary use, and here is an animated version of Bembo’s Zoo, a classic book about animals beginning with each letter of the alphabet, using only the Bembo typeface to form each animal.

- The 2019 book Semicolon: The Past, Present, and Future of a Misunderstood Mark is a 224-page book on the history and usage of the semicolon (and one that has been on my to-read list since it was announced—I’m taking this as a sign it’s time to order it). More: The NYT review of the book and reader reviews on Goodreads, an excerpt from the book at The Paris Review, a lovely piece on the book in The New Yorker, and a WBUR interview with the author, Cecilia Watson.

- Hypnerotomachia Poliphili also inspired a typeface: Poliphilus. Like Bembo, Poliphilus was designed by the Monotype Corporation in the early 20th century. Unlike Bembo, whose design is based upon Griffo’s De Aetna cut, Poliphilus is a facsimile of the type in which Hypnerotomachia Poliphili is set.

- Today’s Bembo roman finds its roots in Griffo’s roman cut of the De Aetna type, however its modern companion italic, which was not included in Morison’s original release, is based not on the 1500/1501 Griffo italic, but on the handwriting of Giovanni Tagliente, a Renaissance scribe.